Step 5: Find cases systematically and record information

As noted earlier, many outbreaks are brought to the attention of health authorities by concerned healthcare providers or citizens. However, the cases that prompt the concern are often only a small and unrepresentative fraction of the total number of cases. Public health workers must, therefore, look for additional cases to determine the true geographic extent of the problem and the populations affected by it. Investigators may conduct what is sometimes called stimulated or enhanced passive surveillance by sending a letter describing the situation and asking for reports of similar cases. Alternatively, they may conduct active surveillance by telephoning or visiting the facilities to collect information on any additional cases. In some outbreaks, public health officials may decide to alert the public directly, usually through the local media.

If an outbreak affects a restricted population such as persons on a cruise ship, in a school, or at a worksite, and if many cases are mild or asymptomatic and therefore undetected, a survey of the entire population is sometimes conducted to determine the extent of infection. A questionnaire could be distributed to determine the true occurrence of clinical symptoms, or laboratory specimens could be collected to determine the number of asymptomatic cases. Information to be collected in a questionnaire includes the following:

- Identifying information. A name, address, and telephone number is essential if investigators need to contact patients for additional questions and to notify them of laboratory results and the outcome of the investigation. Names also help in checking for duplicate records, while the addresses allow for mapping the geographic extent of the problem.

- Demographic information. Age, sex, race, occupation, etc. provide the person characteristics of descriptive epidemiology needed to characterize the populations at risk.

- Clinical information. Signs and symptoms allow investigators to verify that the case definition has been met. The date of onset is needed to chart the time course of the outbreak. Supplementary clinical information, such as duration of illness and whether hospitalization or death occurred, helps characterize the spectrum of illness.

- Risk factor information. This information must be tailored to the specific disease in question. For example, since food and water are common vehicles for hepatitis A but not hepatitis B, exposure to food and water sources must be ascertained in an outbreak of the former but not the latter.

- Reporter information. The case report must include the reporter or source of the report, usually a physician, clinic, hospital, or laboratory. Investigators will sometimes need to contact the reporter, either to seek additional clinical information or report back the results of the investigation.

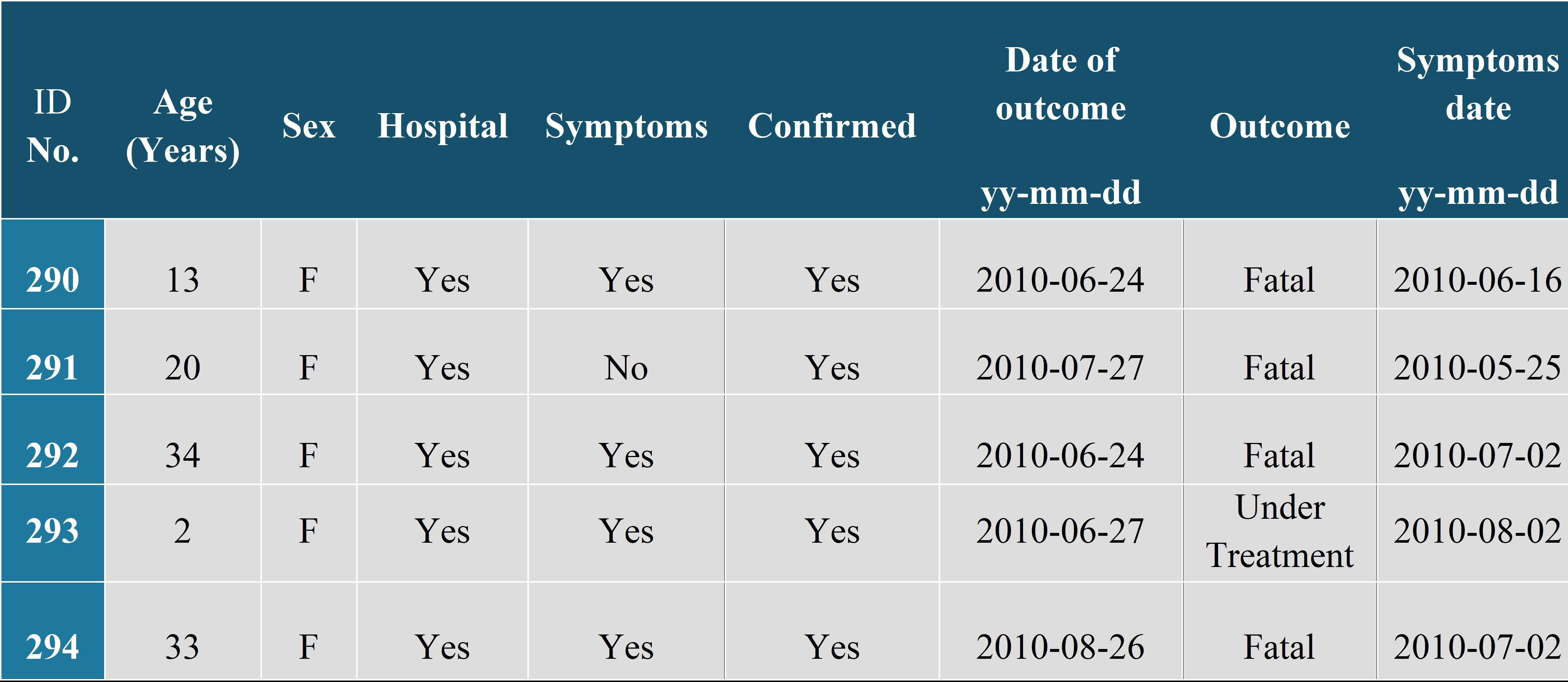

- Traditionally, the information described above is collected on a standard case report form, questionnaire, or data abstraction form. Investigators then abstract selected critical items onto a form called a line listing

Creating a Line List

The information collected on cases by the standard reporting form or questionnaire is traditionally presented as a "line list".

Avian influenza A(H5N1) in humans: September 2006 to August 2010 (Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany, 2011) In a line list, each column holds standard data, such as the unique identification (ID) number, the name, age, sex, case classification, etc. and there is one row for each case. New cases are added to the list as they are identified. The list can be hand written on wide sheets of paper, on a white board or even on individual Post-it Notes. Keeping the information electronically means that the columns may be moved if necessary and others added to include other pertinent information such as exposure, the length of time of the illness, complications, etc. When setting up a line list in a word processor, or spreadsheet program, make sure that the headings will be repeated on every new page. Pay careful attention to how you enter information, especially for dates. The rows can be sorted in any order, by one or more criteria. This type of list serves to: The line list used by local public health investigators will also have names and contact information. Fiebig, L., Soyka, J., Buda, S., Buchholz, U., Dehnert, M., & Haas, W. (2011). Avian influenza A(H5N1) in humans: new insights from a line list of World Health Organization confirmed cases, September 2006 to August 2010. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(32):19941. https://doi.org/10.2807/ese.16.32.19941-enExample of a Line List

References